Textures

We learned that to add more detail to our objects we can use colors for each vertex to create some interesting images. However, to get a fair bit of realism we'd have to have many vertices so we could specify a lot of colors. This takes up a considerable amount of extra overhead, since each models needs a lot more vertices and for each vertex a color attribute as well.

What artists and programmers generally prefer is to use a texture. A texture is a 2D image (1D and 3D textures exist, but they aren't very common) used to add detail to an object; think of a texture as a piece of paper with a nice brick image (for example) on it neatly folded over your 3D house so it looks like your house has a stone exterior. Because we can insert a lot of detail in a single image, we can give the illusion the object is extremely detailed without having to specify extra vertices.

Aside from images, textures can also be used to store a large collection of data to send to the shaders, but we'll leave that for a different topic.

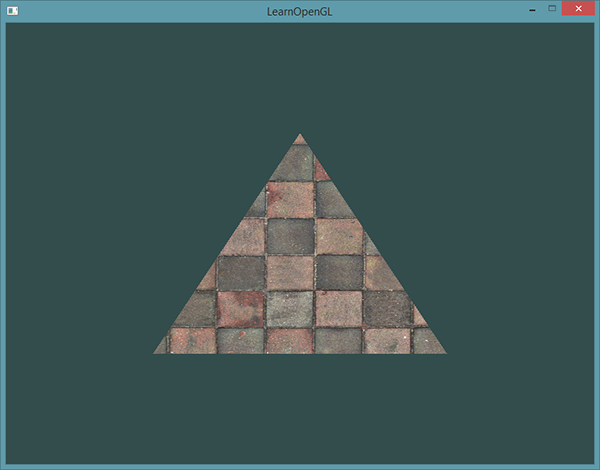

Below you'll see a texture image of a brick wall mapped to the triangle from the previous tutorial.

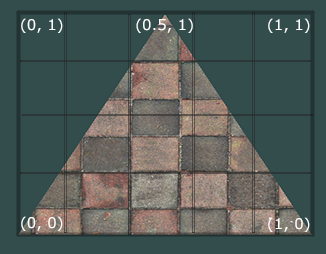

In order to map a texture to the triangle, we need to tell each vertex of the triangle which part of the texture it corresponds to. Each vertex should thus have a texture coordinate associated with them that specifies what part of the texture image to sample from. Fragment interpolation then does the rest for the other fragments.

Texture coordinates range from 0 to 1 in the x and y axis (remember that we use 2D texture images). Retrieving the texture color using texture coordinates is called sampling. Texture coordinates start at (0,0) for the lower left corner of a texture image to (1,1) for the upper right corner of a texture image. The following image shows how we map texture coordinates to the triangle:

We specify 3 texture coordinate points for the triangle. We want the bottom-left side of the triangle to correspond with the bottom-left side of the texture so we use the (0,0) texture coordinate for the triangle's bottom-left vertex. The same applies to the bottom-right side with a (1,0) texture coordinate. The top of the triangle should correspond with the top-center of the texture image so we take (0.5,1.0) as its texture coordinate. We only have to pass 3 texture coordinates to the vertex shader, which then passes those to the fragment shader that neatly interpolates all the texture coordinates for each fragment.

The resulting texture coordinates would then look like this:

float[] texCoords = {

0.0f, 0.0f, // lower-left corner

1.0f, 0.0f, // lower-right corner

0.5f, 1.0f // top-center corner

};

Texture sampling has a loose interpretation and can be done in many different ways. It is thus our job to tell OpenGL how it should sample its textures.

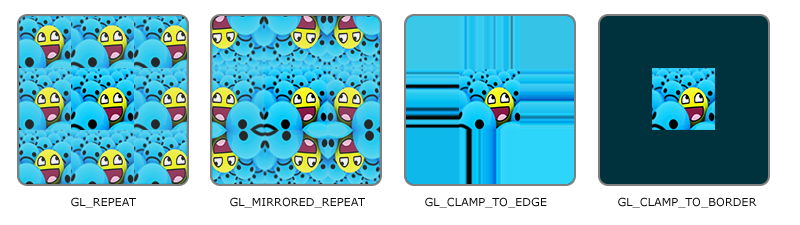

Texture Wrapping

Texture coordinates usually range from (0,0) to (1,1), but what happens if we specify coordinates outside this range? The default behavior of OpenGL is to repeat the texture images (we basically ignore the integer part of the floating point texture coordinate), but there are more options OpenGL offers:

Repeat: The default behavior for textures. Repeats the texture image.MirroredRepeat: Same as GL_REPEAT but mirrors the image with each repeat.ClampToEdge: Clamps the coordinates between 0 and 1. The result is that higher coordinates become clamped to the edge, resulting in a stretched edge pattern.ClampToBorder: Coordinates outside the range are now given a user-specified border color.

Each of the options have a different visual output when using texture coordinates outside the default range. Let's see what these look like on a sample texture image:

Each of the aforementioned options can be set per coordinate axis (s, t (and p if you're using 3D textures) equivalent to x,y,z) with the GL.TexParameter function:

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureWrapS, (int)TextureWrapMode.Repeat);

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureWrapT, (int)TextureWrapMode.Repeat);

Note: You have to cast the enum to int for

GL.TexParameterto accept it.

The first argument specifies the texture target; we're working with 2D textures so the texture target is TextureTarget.Texture2D. The second argument requires us to tell what option we want to set and for which texture axis. We want to configure the WRAP option and specify it for both the S and T axis. The last argument requires us to pass in the texture wrapping mode we'd like and in this case OpenGL will set its texture wrapping option on the currently active texture with TextureWrapMode.Repeat.

If we choose the TextureWrapMode.ClampToBorder option, we should also specify a border color. This is done using the fv equivalent of the glTexParameter function with TextureParameterName.TextureBorderColor as its option where we pass in a float array of the border's color value:

float[] borderColor = { 1.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f };

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureBorderColor, borderColor);

Texture Filtering

Texture coordinates do not depend on resolution but can be any floating point value, thus OpenGL has to figure out which texture pixel (also known as a texel) to map the texture coordinate to. This becomes especially important if you have a very large object and a low resolution texture. You probably guessed by now that OpenGL has options for this texture filtering as well. There are several options available but for now we'll discuss the most important options: Nearest and Linear.

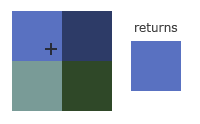

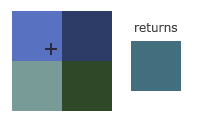

Nearest (also known as nearest neighbor filtering) is the default texture filtering method of OpenGL. When set to Nearest, OpenGL selects the pixel which center is closest to the texture coordinate. Below you can see 4 pixels where the cross represents the exact texture coordinate. The upper-left texel has its center closest to the texture coordinate and is therefore chosen as the sampled color:

Linear (also known as (bi)linear filtering) takes an interpolated value from the texture coordinate's neighboring texels, approximating a color between the texels. The smaller the distance from the texture coordinate to a texel's center,the more that texel's color contributes to the sampled color. Below we can see that a mixed color of the neighboring pixels is returned:

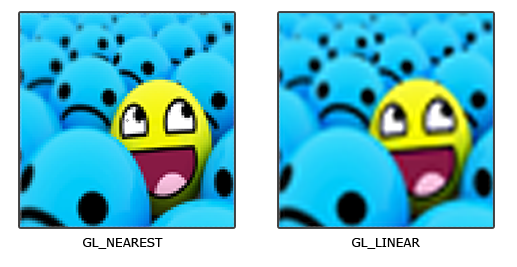

But what is the visual effect of such a texture filtering method? Let's see how these methods work when using a texture with a low resolution on a large object (texture is therefore scaled upwards and individual texels are noticeable):

Nearest results in blocked patterns where we can clearly see the pixels that form the texture while Linear produces a smoother pattern where the individual pixels are less visible. Linear produces a more realistic output, but some developers prefer a more retro, pixelated look and as a result pick the Nearest option.

Texture filtering can be set for magnifying and minifying operations (when scaling up or downwards) so you could for example use nearest neighbor filtering when textures are scaled downwards and linear filtering for upscaled textures. We thus have to specify the filtering method for both options via GL.TexParameter. The code should look similar to setting the wrapping method:

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureMinFilter, (int)TextureMinFilter.Nearest);

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureMagFilter, (int)TextureMagFilter.Linear);

Mipmaps

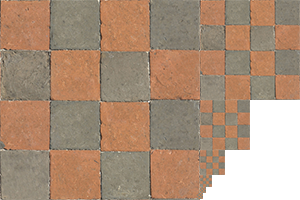

Imagine if we had a large room with thousands of objects, each with an attached texture. There will be objects far away that have the same high resolution texture attached as the objects close to the viewer. Since the objects are far away and probably only produce a few fragments, OpenGL has difficulties retrieving the right color value for its fragment from the high resolution texture, since it has to pick a texture color for a fragment that spans a large part of the texture. This will produce visible artifacts on small objects, not to mention the waste of memory to use high resolution textures on small objects.

To solve this issue OpenGL uses a concept called mipmaps that is basically a collection of texture images where each subsequent texture is twice as small compared to the previous one. The idea behind mipmaps should be easy to understand: after a certain distance threshold from the viewer, OpenGL will use a different mipmap texture that best suits the distance to the object. Because the object is far away, the smaller resolution will not be noticeable to the user. Also, mipmaps have the added bonus feature that they're good for performance as well. Let's take a closer look at what a mipmapped texture looks like:

Creating a collection of mipmapped textures for each texture image is cumbersome to do manually, but luckily OpenGL is able to do all the work for us with a single call to GL.GenerateMipmap(GenerateMipmapTarget.Texture2D) after we've created a texture. Later in the texture tutorial you'll see use of this function.

When switching between mipmaps levels during rendering OpenGL might show some artifacts like sharp edges visible between the two mipmap layers. Just like normal texture filtering, it is also possible to filter between mipmap levels using Nearest and Linear filtering for switching between mipmap levels. To specify the filtering method between mipmap levels we can replace the original filtering methods with one of the following four options:

NearestMipmapNearest: takes the nearest mipmap to match the pixel size and uses nearest neighbor interpolation for texture sampling.LinearMipmapNearest: takes the nearest mipmap level and samples using linear interpolation.NearestMipmapLinear: linearly interpolates between the two mipmaps that most closely match the size of a pixel and samples via nearest neighbor interpolation.LinearMipmapLinear: linearly interpolates between the two closest mipmaps and samples the texture via linear interpolation.

Just like texture filtering, we can set the filtering method to one of the 4 aforementioned methods using GL.TexParameter:

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureMinFilter, (int)TextureMinFilter.LinearMipmapLinear);

GL.TexParameter(TextureTarget.Texture2D, TextureParameterName.TextureMagFilter, (int)TextureMagFilter.Linear);

A common mistake is to set one of the mipmap filtering options as the magnification filter. This doesn't have any effect since mipmaps are primarily used for when textures get downscaled: texture magnification doesn't use mipmaps and giving it a mipmap filtering option will generate an OpenGL GL_INVALID_ENUM error code.

Loading and creating textures

The first thing we need to do to actually use textures is to load them into our application. Texture images can be stored in dozens of file formats, each with their own structure and ordering of data, so how do we get those images in our application? One solution would be to choose a file format we'd like to use, say .PNG and write our own image loader to convert the image format into a large array of bytes. While it's not very hard to write your own image loader, it's still cumbersome and what if you want to support more file formats? You'd then have to write an image loader for each format you want to support.

Another solution, and probably a good one, is to use an image-loading library that supports several popular formats and does all the hard work for us. A library like

stb_image.h and StbImageSharp

stb_image.h is an incredibly widespread library used in c to load images for a number of common formats (png, jpeg, gif etc). There is a port of the project to C# available on nuget in the form of StbImageSharp.

For the following section on textures, we'll use an image of a wooden crate.

Create a new file your project, Texture.cs. Put the following using statements at the top:

using System;

using OpenTK.Graphics.OpenGL4;

using StbImageSharp;

Create a class, Texture, and add an int named Handle as a property. The constructor should take one argument: a path to the image file.

In the constructor, write the line Handle = GL.GenTexture();. This will generate a blank texture for us to use.

Next, add the function Use to your code, containing the line GL.BindTexture(TextureTarget.Texture2D, Handle);. Call that in your constructor just after generating the texture.

// stb_image loads from the top-left pixel, whereas OpenGL loads from the bottom-left, causing the texture to be flipped vertically.

// This will correct that, making the texture display properly.

StbImage.stbi_set_flip_vertically_on_load(1);

// Load the image.

ImageResult image = ImageResult.FromStream(File.OpenRead(path), ColorComponents.RedGreenBlueAlpha);

Now that that's done, it's time to upload our texture.

GL.TexImage2D(TextureTarget.Texture2D, 0, PixelInternalFormat.Rgba, image.Width, image.Height, 0, PixelFormat.Rgba, PixelType.UnsignedByte, image.Data);

The parameters for TexImage2D are as follows:

The type of texture being generated. You can generate 1D, 2D, and 3D textures, but it's rare to need anything other than 2D.

The level of detail. If this is set to something other than 0, you can set the default mipmap as a level lower than the maximum. We don't want that, so leave it at 0.

The format OpenGL will use to store the pixels on the GPU. You almost always want this to be RGBA.

Width of the image.

Height of the image.

Border of the image. This must always be 0; it's a legacy parameter from ancient versions of OpenGL.

The format of the bytes. ImageSharp will always place its images in Rgba, so just use that.

The type of the pixels. Unsigned bytes in this case.

The array of pixels to be converted to the texture.

The image is now generated!

Optionally, we can generate mipmaps. This isn't necessary here, but just for reference, put the line GL.GenerateMipmap(GenerateMipmapTarget.Texture2D) after TexImage2D. That's all you need to do!

Applying textures

Now that our texture is created, we'll need to modify our shaders and vertices to use the texture.

Firstly, replace the array of vertices with this:

float[] vertices =

{

//Position Texture coordinates

0.5f, 0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f, // top right

0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, // bottom right

-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, // bottom left

-0.5f, 0.5f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f // top left

};

Recall above when we discussed texture coordinates and how they worked. We add them to every vertex.

Next, we'll have to modify vertex attribute positions to send the texture coordinates to the shaders.

Replace your call to VertexAttribPointer with:

GL.VertexAttribPointer(vertexLocation, 3, VertexAttribPointerType.Float, false, 5 * sizeof(float), 0);

It's almost entirely the same, just with the stride changed from 3 * sizeof(float) to 5 * sizeof(float) to accomodate the new texture coordinates.

Beneath that, add the following lines:

int texCoordLocation = shader.GetAttribLocation("aTexCoord");

GL.EnableVertexAttribArray(texCoordLocation);

GL.VertexAttribPointer(texCoordLocation, 2, VertexAttribPointerType.Float, false, 5 * sizeof(float), 3 * sizeof(float));

Again, almost the exact same as the last call, just with 2 packets of data instead of 3, and with an initial offset of 3 * sizeof(float).

Now, we need to modify our shaders. First is the vertex shader. The new code is:

#version 330 core

layout(location = 0) in vec3 aPosition;

layout(location = 1) in vec2 aTexCoord;

out vec2 texCoord;

void main(void)

{

texCoord = aTexCoord;

gl_Position = vec4(aPosition, 1.0);

}

We add another input variable, aTexCoord, which will be the texture coordinates. We forward that to the output variable texCoord with no modifications, so that the fragment shader can use it. Speaking of the fragment shader, that's up next:

#version 330

out vec4 outputColor;

in vec2 texCoord;

uniform sampler2D texture0;

void main()

{

outputColor = texture(texture0, texCoord);

}

We see a brand new type of variable, sampler2D. That's the representation of a texture in shaders, to put it simply.

Up to 16 different textures can be bound at once (possibly more, depending on your hardware, but OpenGL requires at least 16). In the next example, I'll show you how to use multiple textures at the same time. For now, though, we don't need to do anything else.

If you've done everything right, you should see the following when you run your code:

Congratulations on drawing your first texture! Next time, I'll demonstrate drawing multiple textures at once.